Meraj Dhir for FashCam

I recently had the opportunity to visit an intriguing exhibition of photographic based works by Latin American/German artist Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann at Corkin Gallery in Toronto’s Distillery District. I also had the privilege of discussing the works with the iconic Ms. Corkin herself.

The exhibition consists of several framed and hung photographs, both colour and black and white, four large-scale colour prints that are suspended as a mobile at the center of the space, and a small sculptural installation. The show is more accurately described as a multi-media installation, though an installation that emerges from, and is firmly grounded in, photo-conceptualist practices.

Pista 01, 2012/2014. Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann

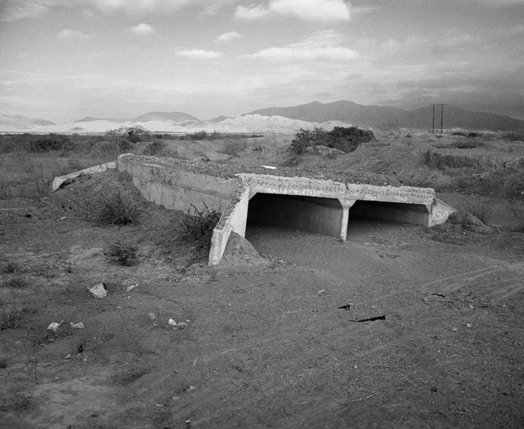

Puente 01, 2012/2014, Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann

As we scan Marroquín’s work, several themes emerge. The exhibition is based on the theme of a road trip through Peru, and so the photographs can be viewed sequentially as various stops and sites along a geographic progression. The photographs’ strong formal and pictorialist qualities assert themselves as singularly crafted photographic images. Take for example, Pista from 2012. We are presented with what seems like a rocky mountain range where the asphalt leads to a sudden dead end. As we view the image more closely we can see that the jagged V-shape in the rocky quarry has been produced through some form of man made industrial intervention. Instead of natural landscape then, or a place where civilization comes to an abrupt halt abutting the natural world, we can apprehend this picture as a documentation of something like a site specific and anonymously produced sculpture. Indeed the picture’s starkly assertive bilateral symmetry, the strong zip produced by a center line on the surface of the asphalt leading our eye up the geometric center of the image, and the perspectival cues provided by the white road marks flanking the asphalt, all function as pictorial cues declaring the work’s robustly modernist sensibilities. The allusion to anonymous sculpture here provides a possible thematic thread tying several of the works together.

Colectivo 44, 2012/2014, Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann

Colectivo 13 (La gata), 2012/2014, Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann

In addition to other motifs of industrialized ruin: long out of use bridges and eerily empty sites, roadside signs or shacks, the other major theme of the exhibition are the “colectivos,” which names the practice of repurposing classic American cars once assembled and sold in the region, and using them as makeshift public transportation vehicles. Indeed the owners of these cars drive to villages where public transit is not offered and fill them with paying passengers. In this sense, Marroquín’s lens functions to document the repurposing of a symbol of American individuality and industrial triumph into a peripatetic mode of anonymous and collective social production. The depiction of cars in modern art has a long history and reaches its apogee in Pop art, especially in its British variant and the work of Richard Hamilton. So too, within photo-conceptualist practice we can cite Ed Ruscha’s documentation of Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations from 1962. But Marroquín is less interested in the erotics of the automobile (usually gendered female) as a displacement for the human body than he is in the car as node for collective social activity.

That said, there is another impulse at work in the “colectivo” series and this entails their highly cinematic quality. The artist uses precise compositional principles and artificial lighting to boost the dynamism of his scenes. In Colectivo 44, for example, Marroquín has staged the cars on an oblique diagonal suggestive of a chase and speed of movement. The colectivos seem like either props from a seventies thriller starring Steve McQueen or a restaging of some action film spectacle. Marroquín is a sophisticated colorist as evidenced by Colectivo 13, where his framing of the gold car against the teal-blue sky and wall pushes the optical buzz created by the proximity of two complementary colors. Photographing many of his scenes at either dawn or dusk further boosts the moody, dramatic qualities of some of the pictures. Such a narrativized interpretation of these images is available to us precisely because of the inherent absence of any human presence from nearly all the photographs. Moreover, the scenes lack particular identifying cues that might allow us to easily recognize what is happening in some of the pictures. Are these cars staged for the viewer, or are they snapshots of events occurring independently of the photographer?

Paisajes diversos 11, 2012/2014, Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann

Paisajes diversos 03, 2012/2014, Andrés Marroquín Winkelmann

The series of four photographs hanging from the ceiling in the exhibition space, the so-called, paisajes diversos, present a formal departure from the other works. Large, diaphanous color fields, these images are pure abstractions. Without the titles we would be unaware that they are in fact photographs of the ocean, the rainforest, the desert and the mountains respectively. I am tempted to see these images as the culmination of Marroquín’s “road trip” his “final destination.” Here, the artist has turned the focus on his lens to entirely blur the elemental motifs before him. These images find an interesting modernist parallel in late nineteenth century French Impressionist attempts to represent landscapes through a sort of “disembodied eye,” and capture a pure opticality, unhindered by acculturation or compositional bias and aesthetic criteria. Impressionist artists such as Monet strove to paint as if seeing for the first time, and various myths of patients who had been born blind and regained their site in old age fuelled this speculation about what such an “innocent eye” would see. And so Marroquín’s final images in the exhibition present scenes that, while mediated through the mechanized apparatus of the camera, are to some degree untouched by human subjectivity.

The exhibition ends with a series of identically repeated sculptures that display corrugated metal panels, or calaminas used as roofing panels in various architectural structures such as roadside huts, homes and commercial sites. The sculptures function as a sort of coda to the exhibition, but more importantly as a hermeneutic key to unlocking Marroquín’s artistic aspirations. This bringing together of geometric abstraction and the neo-avantgarde trope of the readymade reveals the photo-conceptualist basis of Marroquín’s art practice. Educated in Berlin, we can see certain strains of influence on Marroquín from the work of an earlier generation of German artists such as Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth.

The introduction of the corrugated panels as sculptural readymades within the exhibition introduces the possibility that the photographs, despite their purely pictorialist qualities, are themselves documents of anonymous and site-specific sculptural arrangements. Such an interpretation gains force when we consider that in almost all cases the photographs lack human presence and subjectivity and in many instances the bridges, signs and cars are centered, arranged and lit by Marroquín so as to highlight their robust formal dimensions. In this view, the photographs become documents of both collective social appropriation and anonymous, site-specific sculptural arrangements.

Despite the repetition of a set number of pictorial motifs, what distinguishes Marroquín’s work from Conceptual art is its emphasis on pictorial values and a carefully choreographed mise-en-scène –that is, his works are primarily presented as traditionally crafted, single image prints. If conceptual photography is defined by serialism and deskilling, Marroquín’s photography aims at reskilling and aspires to obtain a high level of artisanal accomplishment, and herein lies the paradox of this photographic project. On the one hand Marroquín’s photographs are documents of diverse geographic terrains, scars wrought by industrial interventions of various sorts, and evidence of collective social appropriation. On the other hand, because of their carefully choreographed mise-en-scène some of the images are evocative of stills from a Hollywood movie, pure spectacle or commodity fetishism.

Each photograph in the series asserts its formal independence from the rest and encourages the viewer to mobilize any different number of interpretive schemata. Here we see how the principle of exclusion, what the artist has subtracted from the scene, works to imbue each picture with an inherent ambiguity and interpretive instability. Subtracted of human presence, we are only provided with enough contextual cues so as to infer the bare minimum of what each scene represents. To the uninformed observer these images could have been taken in any number of South American locales or even the American southwest. Perhaps a more culturally savvy and geographically sensitive viewer might recognize the scene through some minute detail of local object or terrain. This raises a problem given the photographs’ claim for geographic and historical specificity. The almost phobic prohibition of the subject in Marroquín’s exclusive focus on landscape and ruins of industrialization suggests that in order for the aesthetic values of these works to assert themselves, social and historical context has to be excised from the images. This lack of cultural specificity allows the photographs to function as ideologically undisturbed objects for artistic appreciation. This problem remains unresolved in the exhibition and it is perhaps precisely the very lack of human presence in the works that reasserts itself in the images as a lack, a ghostly presence haunting their melancholic presentation.